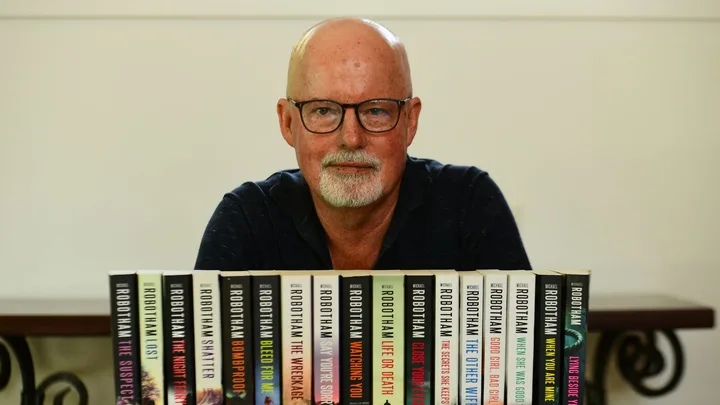

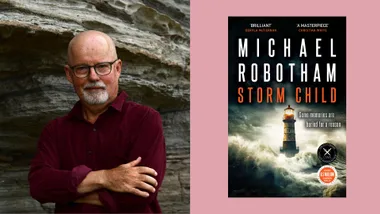

In 2020, Australian crime writer Michael Robotham won his second Gold Dagger for his novel Good Girl, Bad Girl about complex criminal psychologist Cyrus Haven and damaged teenager Evie Cormac. His new book Storm Child is the fourth book in the Evie and Cyrus series.

AWW: You’ve said Evie Cormac is one of your favourite characters to write. What do you love about her? And where did she come from?

Michael: I love that she’s such a conundrum. She is obviously so damaged and so broken and self-destructive and yet also incredibly brave and feisty. I guess she fascinates me because this ability that she has to tell when someone is lying – it is a curse, as she says. And each time that I go back to Evie it really is to explore what would it be like to go through life having this ability. Knowing the damaging power of three little words like ‘I love you’ or ‘I miss you’ to someone like Evie. And so, each book is an exploration, really, to see how does she get a job? How does she begin a relationship? How does she hold a friendship together? Because we lie all the time. Every one of us lies all the time to the people we love to keep our friendships and our relationships and families together.

As she gets older, she’s going to begin to potentially irritate people, but they’ve got to remember where she’s come from and what she’s been through, and how damaged she is. And that’s why she will sabotage her own happiness at times. And also, she makes me laugh. She does things that genuinely make me laugh. It makes her sound like a real person but in a sense, I treat all my characters as real people.

They do feel real. They feel well-rounded and they leap off the page.

That’s the trick. My past career was first as a journalist then I was a ghost writer and each time I worked with someone as a ghostwriter my job was to bring them to life on the page and to make a real person live and breathe on the page. I treat my fiction in the same way. My fictional characters, I want to breathe life into them. I want people to fear for them and to cry for them and to cheer for them and to believe that they’re as real as I do.

Evie appears in an earlier novel, Good Girl, Bad Girl. I was going to ask if it is more fun to write good characters or villains, but very few of your “villains” are pure villains.

In terms of villains, they’ve all got a reason. It doesn’t forgive what they do but it explains what they do. In my ghost-writing days I worked with a man called Paul Britton who was a pioneer of offender profiling in the UK. He worked on celebrated cases but every instance, when you unpack the history of the villain in those real-life stories, there was a history of neglect or abuse or violence.

As I say, it doesn’t forgive what they do but it explains what they do. One of the lines I’ve always lived by in my writing is that society gets the monsters it deserves. Invariably the villains in real life, they’re created by circumstances. They’re not just born that way.

I think nowadays crime fiction is far more nuanced. It’s not like watching an old western where the villains wore black hats and the heroes wore white hats and someone was just bad for the sake of being bad. It’s a bit like the case of giving your heroes flaws, you also have to give your villain a backstory and a context.

Storm Child is part of a series, but I’ve heard you speak about wanting each novel to work as a stand-alone, and so as you introduce Cyrus and Evie, you want to give enough detail to clue in a reader who is meeting them for the first time, but not so much that it bores a serial reader.

I want people to go back and read the early books. I don’t want to give them the full back story of those early books I want them to go back and realise these are complete books and I will learn a lot more by reading them.

That alone sounds challenging, but I wonder, is it a bigger challenge not putting information in the later books that spoil the earlier books? How do you navigate that?

That’s exactly the plan. Occasionally I’ll pick up a new writer who’s writing book two or book three of a series and the plot of book two or book three will depend upon what happened at the end of book one and you have to give it away and I think that’s just pointless.

I want people to pick up each book and know that no matter where they are in the series they feel as though they haven’t missed out on anything.

What’s often amazing, if you ask people what their favourite book is in the series, it’s not necessarily the first one, but it’s the first book they read in the series and that could be book three or book four. It’s the one that first brought them in and therefore it had greater power, and that’s the one that they always remember best.

You find a new clever way to re-introduce characters and tell their backstory without it being an information dump. You want to give the background to Cyrus and his family tragedy and you want to give a background to how Evie was discovered hiding in a secret room where a man had been tortured to death, but you don’t want to give all the details, so you find new, interesting ways of reintroducing them in a fresh way and not revealing the full details that happened in earlier books, certainly not the mystery.

It must be a challenge and I’ve got to say, I was really shocked when I heard you don’t plot your books because Storm Child felt so watertight, and intricate.

That was the challenge. When I wrote Good Girl, Bad Girl and I put Evie as that child discovered in that secret room, I finished that book having no idea who put her in that room. Still. I began writing book two and I had to live with the clues I planted in book one. And if people ask me, do you know what’s going to happen? I’ll go no. I still don’t know who put her in there. But I’ll work it out.

That sounds like half the fun.

If it surprises me, it should surprise the reader, because if I don’t see it coming then the reader shouldn’t see it coming.

I heard you speaking about your first book, The Suspect, which sparked a bidding war at the London Book Fair in 2002. You were saying you hadn’t finished it, and when it sold, you thought: Oh dear. I’m going to have to come up with an ending now.

I didn’t know how it ended. It was a quarter of a book that they bought. It was exciting and terrifying in equal measures.

Author Toni Jordan once told me some writers are knitters who work sequentially, one scene after another, while others are quilters, who writer vignettes they stitch together. Which are you?

I’ve got one I use which I prefer. It’s pioneers and settlers. See a pioneer is the sort of person who charges forward and plants a flag, saying I’m going to come back and build a town here. As in, write a chapter about this. Then they charge off and plant another flag, and say I’ll come back and build a town here. And in that way, they charge forward. Whereas a settler plants a flag, builds an entire town and says, oh, I might go and settle another place now, and he goes off and plants another flag. And so, I’m a settler, I write each chapter not knowing where the next settlement’s going to be.

As long as when I get to the end of that chapter, I can see that I’ve got four or five different ways for the story to go, I’m pretty comfortable. But if I see only one way the story can head in, I get very nervous because if that’s off a cliff – then I’m going to have to go back and throw many, many words away and start again. Eventually you’ll plot your way through.

E. L. Doctorow said it best when he talked about writing the way I write. It’s like taking a long journey at night and you can only see as far as the headlights show you, but you know you can get to the end of the story even though you can only see a little way ahead.

Even your minor characters have such vivid, real traits. A woman with a cobweb of lines around her mouth. A paramedic with a smudge of lipstick that highlights how pale her skin is. I was curious, as you’re walking through the world are you cataloguing traits, and tucking them away to use in your fiction? Or do these descriptions come from somewhere else? Do you conjure them?

A bit of both. I remember there’s a wonderful Hemingway line: If you can describe the character in a single line and you know that the reader can go one hundred pages and as soon as you mention that character again they’ll go: oh! That’s that one. Hemingway described once meeting someone who had a dimple deep enough to drop a marble into, and suddenly that’s all you needed. That detail. Suddenly, that was the dimple person.

I guess that’s the journalist in me. I was always a feature writer, and it was that ability to find one little feature of a person that’s going to plant that person in the reader’s mind.

The world that Evie and Cyrus move through is very vivid. At St Andrew’s Dock Cyrus describes rusted metal flaking off in his hands as he descends a ladder, and you use sounds and smells to great effect. Do you go to these places, and walk around and soak them up, or do you build them from your imagination and memory?

Where possible I go to the places. That’s the journalist in me. I actually got into trouble at one point. I had lawyers that had to legal a novel for me, and they asked me whether a particular farmhouse that I described in very vivid detail whether thar farmhouse existed and was exactly where I’d described it. I said, ‘Yeah, of course.’ And they said, ‘You have to change it because someone lives in that house, and you’ve just put three bodies in their front room.’ So I actually have to alter details in the end because I’m too accurate in describing place.

In this case I spent time in Scotland and I spent time in Cleethorpes and I spent time in Nottingham. Actually, I’m just back from three weeks in London where I was walking the streets for the next book. I often do it after I’ve done the writing. Because I don’t plot my books in advance there’s not much point doing a whole lot of research beforehand because I don’t know where I’m going to want to be. What I’ll do is I’ll write the book and then I’ll go to the locations and add a few little details.

Your research regime must be rigorous. Do you have some experts on speed dial who you can call and check a fact with?

No, it’s just me really. I did interview, in the UK and Scotland, I talked to harbour masters and to fishermen and to Royal Lifesaving crews and coast guard people. I did talk to a whole lot of people when I was there, getting down the details. In the most part I try really hard right down to studying the tidal charts. If a boat sank where it sank, where would be bodies wash ashore. I know that potentially I’ll choose the wrong time of year and the tides wouldn’t have done that or that month it was a full moon and it wasn’t a king tide. I don’t know … I do it as much as I can knowing I can’t be perfect.

How did being a ghostwriter prepare you for writing fiction?

Capturing voice. Everyone I ghostwrote for had a unique voice and if I did my job properly people that had known them their entire lives wouldn’t recognise my fingerprints on the manuscript. It would look and sound exactly like Geri Halliwell or Lulu or whoever I was writing for.

So, the process for me when I come up with a new character is about creating a voice for them which, just as I said, I believe. I bring them to life and once I have their voice, I feel like they’re real people.

After my first novel The Suspect twenty years ago one of my main characters, Joe O’Loughlin’s wife, was pregnant and I had readers contacting me in the few years that followed asking me if she’d had a boy or a girl and when I said I don’t know they said, ‘But surely she’s had the baby by now?!’ The idea that readers just buy in that these are real people that I have a beer with every Friday afternoon or go away with on weekends is very flattering. Cyrus Haven’s had several marriage proposals.

I’ve heard you refer to your writing room as your Cabana of Cruelty. Where does it get its name, and is it decorated with anything to help you get into a cruel frame of mind?

It gets its name because in our previous house I had a basement office that my children referred to as ‘Dad’s pit of despair’ and when we moved to the new house, I got the office in the garden, it became the cabana of cruelty. It’s not full of torture equipment. Although I do think that in their adolescence they would seek advice is they should venture up to the cabana of cruelty to hit me up for money or the car or whatever they wanted. Because, what sort of mood is dad in? Has it been a good day or a bad day in the cabana of cruelty? It’s just full of books and research books and other books and it’s normally incredibly untidy.

Buy Storm Child here and read our review here.