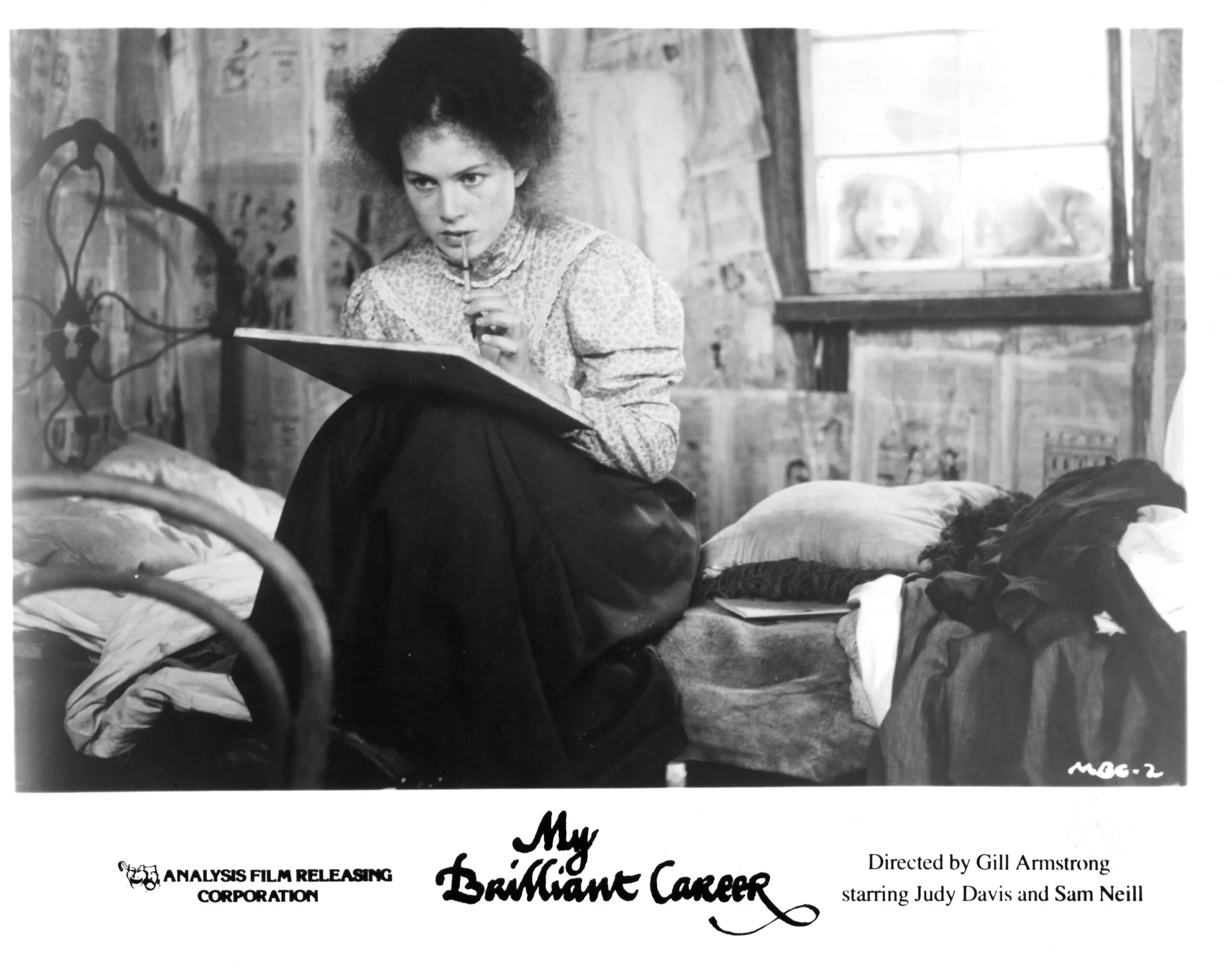

With news that a TV adaptation of Miles Franklin’s novel, My Brilliant Career, has begun filming in Adelaide, we revisit our story celebrating the 40th anniverary of the Australian film. Read on for tales from the now-world famous faces of the cast as they reflect on the tears and triumphs that went into making a classic.

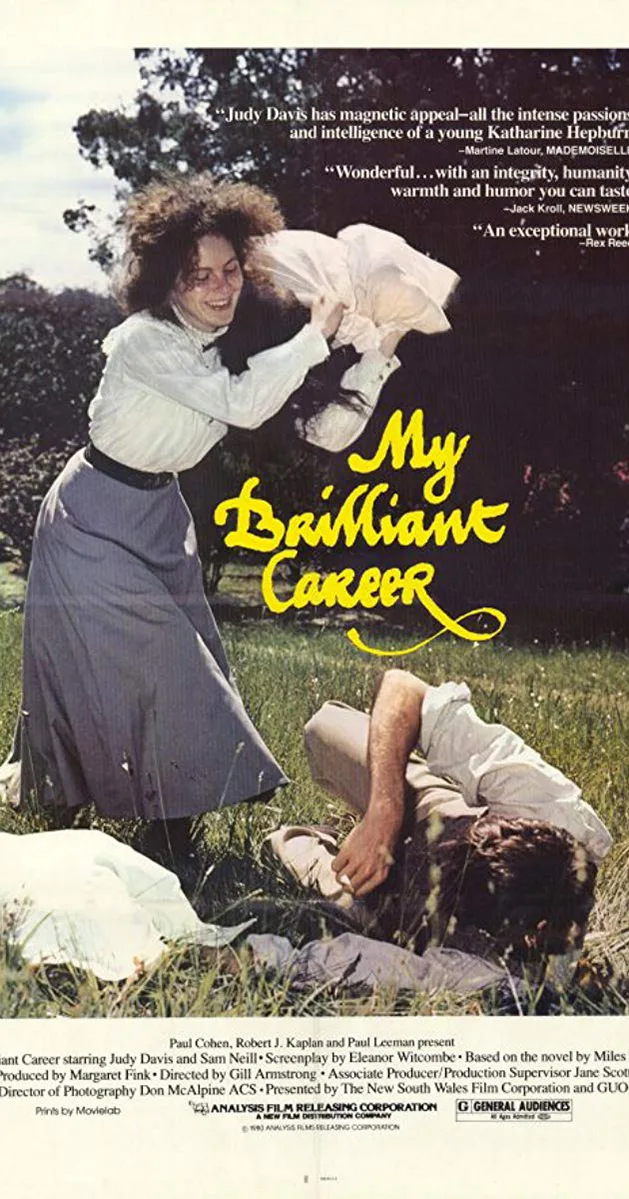

When Gillian Armstrong stood on the steps of the Palais des Festivals for her moment of glory, she was wearing a dressing gown. It was 1979 and her film My Brilliant Career was only the second Australian film ever to be in competition for the coveted Palm d’or. She, the film’s star Judy Davis and producer Margaret Fink were the toast of Cannes. And there she was in a self-customised op shop outfit.

“I was so naive I didn’t even know what the competition was. I had no idea it was a really big deal for a film maker to have their film selected. It took about 10 years to realise it is amazing to ever be in competition in Cannes,” Gillian admits.

When she found out she had to wear an evening dress for the screening, she simply didn’t have one. She didn’t know that Cannes was the home of haute couture red carpet.

“So I got a 1940s dressing gown from the op shop and I cut the sleeves and the back out of it and put my hair in a side ponytail. I had no idea.”

My Brilliant Career had been one of those moments when all the elements align into that rarest thing – alchemy. When all the right people are in the right place and magic happens.

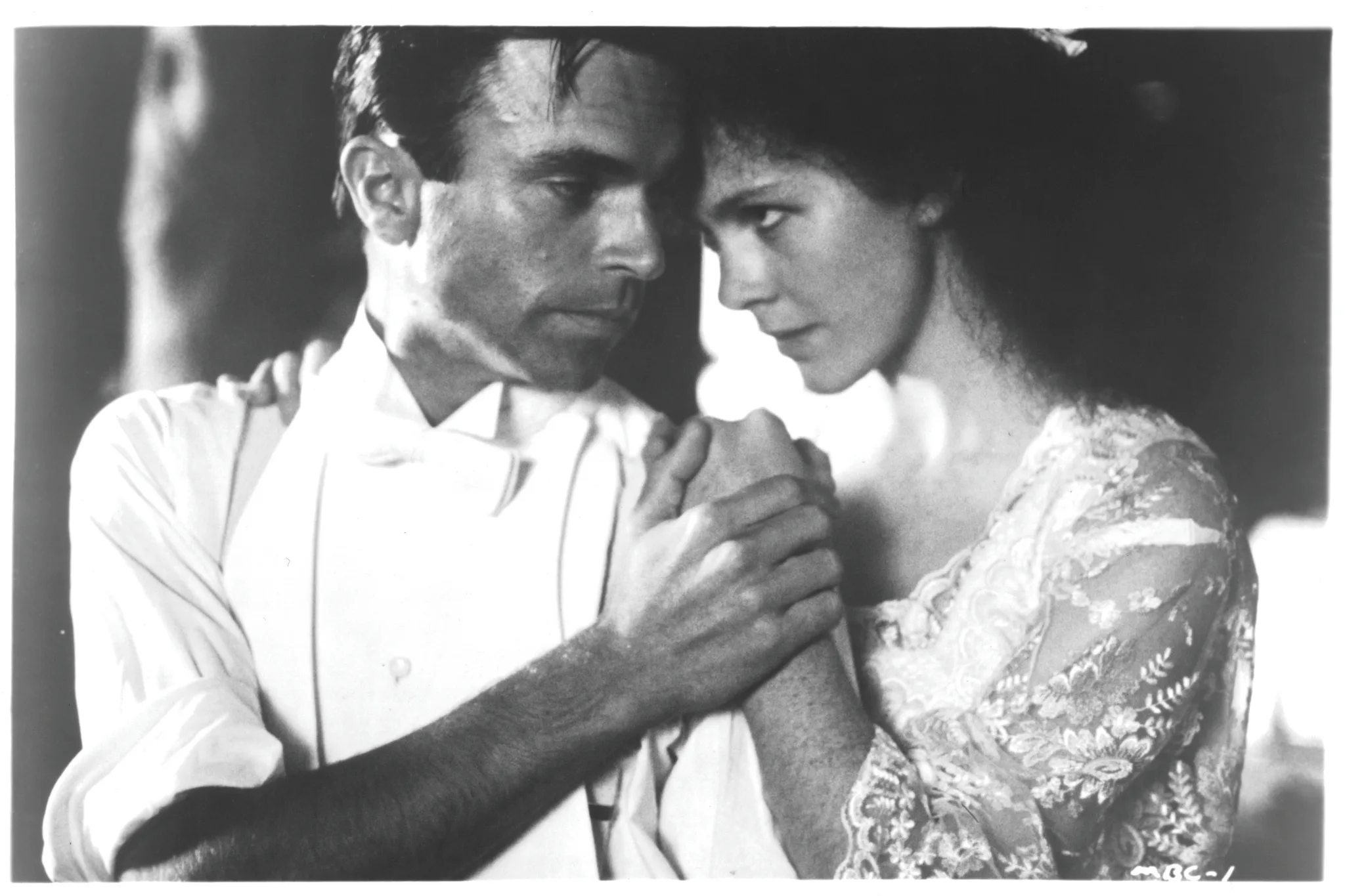

All these years later, at its 40th anniversary screening at the Launceston Breath of Fresh Air film festival, a remastered My Brilliant Career is timeless, a classic, an iconic film. But its impact could not have been predicted in 1979. It’s origins were not auspicious. Its director, Gillian Armstrong, was only 27, a young woman making her first feature film. The lead actors, so famous now, were completely unknown. It was the first film for Judy Davis, who at 23 was just out of NIDA, and the second for Sam Neill, who until then had been a “threadbare hippie” documentary maker.

But it was a picturesque rebel yell, an eloquent cry for freedom, a film about a woman breaking free of class and gender expectations, an elegant free spirit of a film, a rush towards independence in beautiful period detail.

Sybylla Melvyn (played by Judy) is a Jane Austenish character – clever, precocious but without the beauty or wealth required to snag the desirable husband. “Useless, plain and godless,” says her mother. Her problem was “being a girl” and being “born ugly and clever”, she wrote.

In true Austen style, she meets a rich, handsome man and is warned that he is above her station and could never marry her. But he is captivated by her spirit and proposes. It is here that the story veers dramatically from the Austen formula of a wedding and happy ending in a vast country estate.

Sybylla is falling for Harry – there is undeniable chemistry – but she doesn’t want to be married. She wants to be a writer, she wants a much bigger life than merely being a country wife. She wants a career. “I can’t lose myself in someone else’s life when I haven’t lived my own yet.” She says “no” to her suitor – one tiny word that echoed around the world and joined the second wave of the women’s movement of the late 1970s.

“Virtually,” says Margaret, “she is saying I want a career and I’m ambivalent about marriage but if it is a toss-up, I want a career.”

The author Miles Franklin’s struggle for emancipation had happened 70 years earlier, decades ahead of its time, when a woman needed a man to survive. A single woman was a pitiable creature, a spinster. She was only 16 when she wrote My Brilliant Career, which was published in 1901. She had grown up on a property called Brindabella Station in New South Wales, on the edge of the Snowy Mountains, where she assiduously wrote in diaries and yearned for a life of literature and art.

“Here is the story of my career,” the film starts. “My brilliant career. I make no apologies for being egotistical because I am.” Outside the farmhouse, a dust storm is raging but Sybylla is oblivious, lost in her own imaginative world.

Because the novel was deemed too close to autobiography, Franklin withdrew it with an embargo of 50 years before it could be republished. Margaret read it on its rerelease in 1965. “I was drawn to it because it is feminist,” she says. “That is why it is still powerful.”

Margaret was at the centre of Sydney’s creative world, her home and salon attracted the most brilliant people of the time: artists, actors, authors, lawyers. She has been an exceptionally close friend of Germaine Greer for decades, ever since they were both part of the Sydney Push. “I was born a feminist and that is just it.”

Today she believes she has not been properly recognised for what she brought to that film. “My Brilliant Career is my film, it really is. It is a question of attribution. Yes, Gillian did a great job, she has wonderful visual taste. But who chose the project? Who found the screenplay writer, who found the musical director, who found the production designer, the actors?”

For her part, Gillian says, “Margaret and I shared the same taste. She was a great back-up. She bought the book and thought it could be a movie and, like all producers, helped find me the most wonderful crew and cast. But ultimately the main creative decisions are made by the director. Perhaps Margaret should give herself more credit for her selection of the director,” adding that “it is very sad, we were great friends.”

Gillian was working in the props department on Margaret’s first film, The Removalists, when Margaret gave her the book. “I was a very pretentious film school graduate who was anti-Australian literature,” Gillian says now. But, “I related to a young woman who wanted more from life.”

Margaret was determined to make the book a film, but from when she first set out to raise the money right until the film’s release there was pressure to change the ending. David Williams, general manager of Greater Union, said he would give her one-quarter of the budget if she got Sybylla to marry Harry. “Women want a romantic ending,” he said.

“I said I was I making it because she says no,” recalls Margaret.

Gillian was the first Australian female to direct a film in 48 years. “People were saying, ‘Well, the director of photography will be directing because a girl doesn’t know how to shoot a film,’” she says. “They thought we’d never understand the technique about lenses and shots.”

But Gillian knew this film had to be directed by a woman. “I knew a man would totally stuff it up,” she insists. “I knew every woman stands in front of the mirror at age 15 and thinks ‘I am ugly, I am not beautiful enough’. That is what it is like being a woman. I had to do it. It needed to be told from a woman’s point of view.”

Margaret was in a shop in San Francisco when she heard Schumann’s Scenes from Childhood, which so perfectly underscored Sybylla’s wildness within the repressed world where she lived. “I said to Hannah [her daughter], quick, write that down. Then I played it for Gillian on the piano.” Judy, an accomplished pianist, would play it herself in the film.

Sam Neill had come to Melbourne from New Zealand to promote the film Sleeping Dogs.

“We had a press conference and one reporter turned up by mistake – he was a sports reporter,” Sam laughs.

“We had looked at a lot of people for the leads,” Margaret says. One day she opened The Australian newspaper, saw Sam’s photo and rang Gillian. “I’ve found Harry Beecham,” she said. “I was so excited. It was like finding a lover. I got him to come around to [my house] just to make sure – face to face – that I was right. I opened the door and there was Harry Beecham, at last. I couldn’t believe my luck.”

For Sam, Australia in the late 1970s was a revelation. “There was rock and roll in every corner pub, and so many interesting people,” he recalls. He went back to NZ, resigned from his job, sold his house and came to make the film.

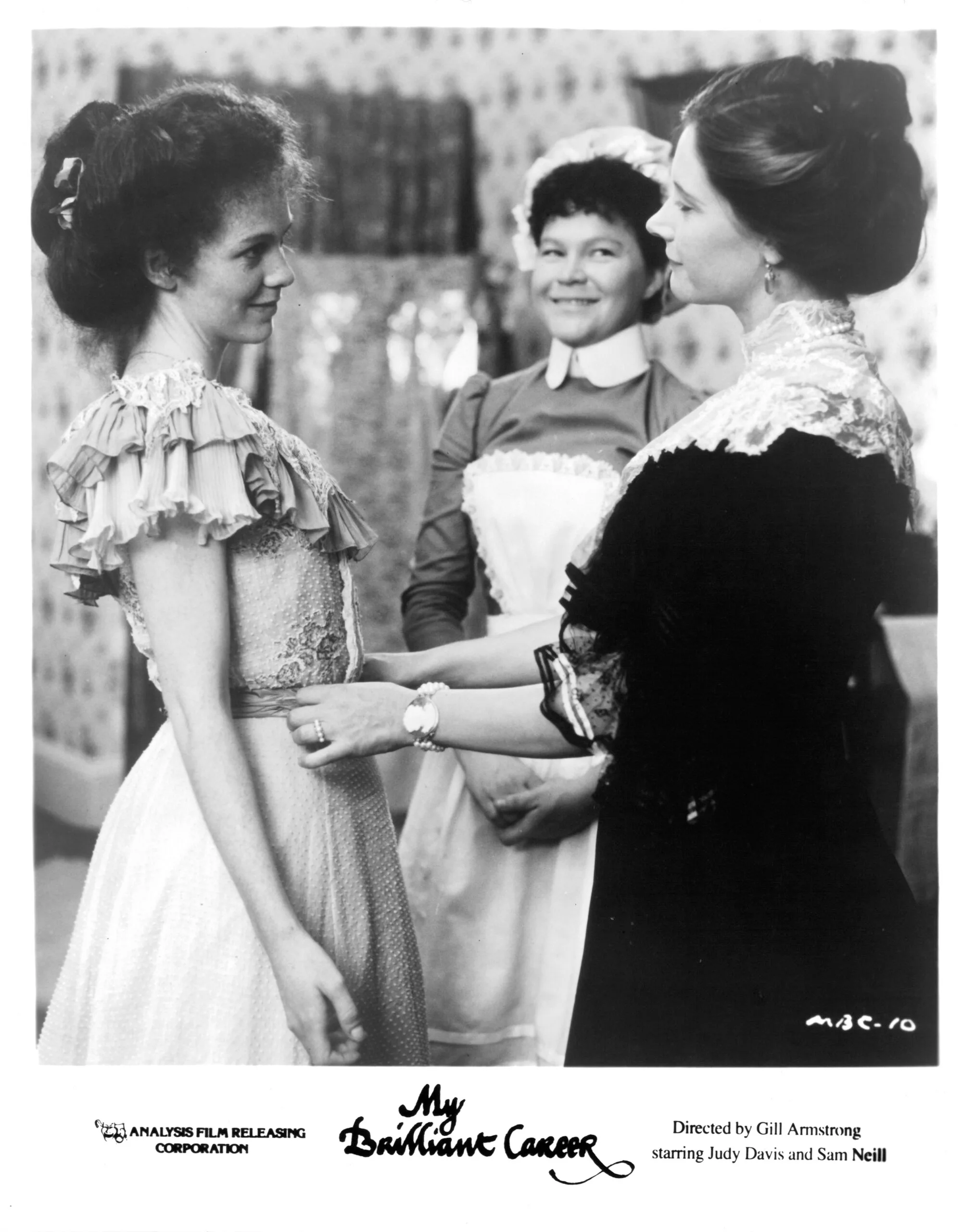

Margaret and Gillian had seen a lot of girls for the part of Sybylla – one had even come close. Margaret went back to theatrical agent Hilary Linstead. “I said, ‘There was another girl on that list. Why didn’t we see her?’”

Judy Davis had been interstate but was back in Sydney, rehearsing a Louis Nowra play at the Paris Theatre. “I went straight to the rehearsal, waited for her to finish and took her to Clay’s Bookshop. I bought a copy of the book, crossed out ‘My’ and wrote ‘Your Brilliant Career’. That sort of talent is so rare. I was lucky.”

Says Gillian, “At Judy’s audition, Margaret, Hilary and I all agreed – she was extraordinary.”

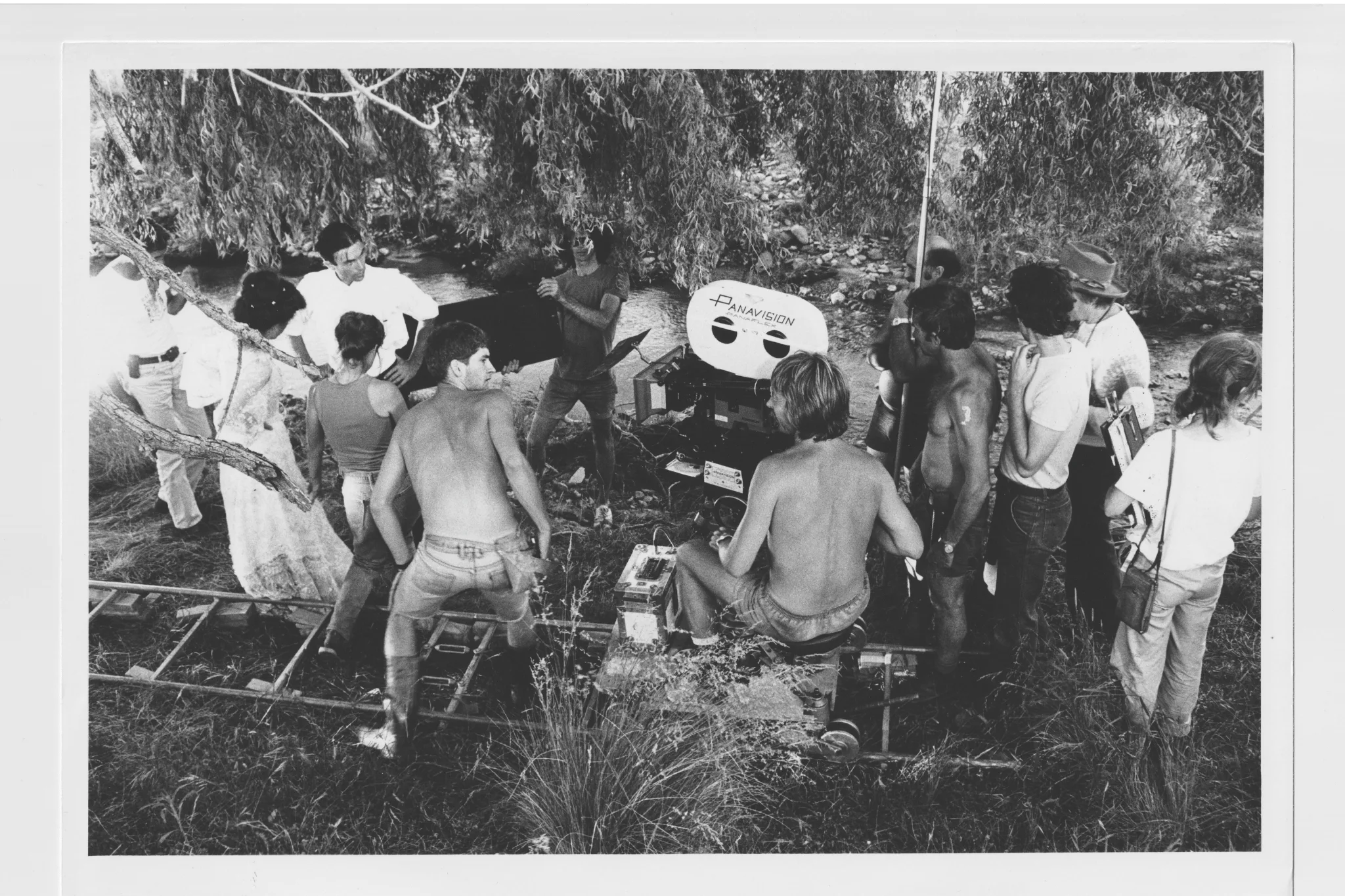

When filming started, Gillian admits, “I was definitely scared. As a director, it’s like going to war. Then it becomes about survival and just trying to get all the shots and keep them going.”

What lingers from My Brilliant Career all these years later is the sheer beauty of it, the loving light-filled evocation of rural Australia at the start of the last century.

“We were very, very ambitious for the look of it,” says Gillian. “I am a perfectionist. I only want to shoot my scenery in the morning or the afternoon. I want the best light. Don [McAlphine, the cinematographer] and I walked around every single location, everything was planned – the colours of the costumes and what they looked like against the wall. I didn’t want wishy-washy, I wanted dark shadows.”

Sam, who had never ridden before, remembers his “tricky” horse. “It was gorgeous looking, but a thoroughbred with half a brain. It would only turn right because it was from Victoria and they go the other way on the track. I grew to hate that horse.”

Don, who had come from Breaker Morant and would go on to be one of the most in-demand cinematographers in the world, says, “Gillian knew exactly what she wanted. She was definite about it. She’d get in my car after the tension of the day and virtually collapse into tears.”

Judy told the ABC’s Virginia Trioli, “She was struggling with a crew that was a bit hostile, she was a young woman being given a large budget.”

It was Don who came to the rescue when, halfway through the film, the art department had gone over budget and there was no money left for the giant wind machine to create the dust storm that is the film’s dramatic opening.

Gillian was lying awake at night worrying. “I was getting more and more depressed,” she says. “I rang Margaret. She said, ‘There is no more money, darling.’ Then I thought, what if the camera stayed inside and we had the dust storm outside the windows? Don said, ‘I can do a really big wheelie in my car’. Every member of the crew was there with shovels, creating dust.”

Don remembers Judy as insecure. “I think she had some resentment that she was working in film and not on the stage. She was a little bit aloof.”

Decades later when they worked on The Dressmaker, he says, “It was the reverse of all that.” Judy has said that she had only seen herself working in the theatre, but couldn’t get work.

What Gillian had hoped for the film was that it would do well in Australia. That it wasn’t a “disgrace”. It was so much more.

My Brilliant Career won six Australian Film Institute awards, two British Academy awards and Oscar and Golden Globe nominations. Even in the late 1970s, saying no to a lovely man offering financial security was radical.

“It connected with people around the world and is one of the reasons it became so successful,” says Gillian. “Women all over the world have come up to me and said, because of your film I became a writer, because of your film I followed my dream.”

When the famously tough Cannes audience stood and applauded, Gillian thought their publicist had organised it. It didn’t start sinking in until the next day. “Judy and I were walking down the Cannes streets and people were shouting ‘congratulations’.”

Sam couldn’t go to Cannes, by then he was tied up on The Sullivans. “I was Kitty Sullivan’s boyfriend, I ran away with her to Sydney and Dave Sullivan came up and smacked me on the nose,” he recalls.

But there was some consolation. When My Brilliant Career came out, “I was a gay icon for about five minutes,” he smiles. “I was the cover guy of Gay News.”

Judy declined to talk to The Weekly about the film that launched her own brilliant career. “On the flight on the way home,” says Gillian, “Judy told me she had never liked the script and she had never liked the character but everyone had said she should do it. She has never really liked the film or wanted to see it. There were lots of times she had issues and questions about things so then it all made sense. She is incredibly bright and smart, it just wasn’t her thing.”

Previously speaking to Geraldine Doogue, Judy said she had not liked the loss of control, that she “felt a bit like a puppet”, and “I could never really understand the fuss about it. I found the feminist statement simplistic.” She didn’t understand why Sybylla couldn’t just have her man and a career.

She told the ABC’s Virginia Trioli, “It was horrendous from start to finish. There was a funny atmosphere on that film. They did that to my hair [frizzled it up] without asking.”

Says Margaret: “Judy has denigrated this film. She just thought it was a girls’ film. She is a difficult personality, it is no secret. She can be dismissive.”

Yet seeing the film again feels very emotional. The stars were so young and talented.

“It was lovingly crafted,” says Sam. “Gillian directed it with great acuity and empathy. And Judy Davis was obviously a star.”

Everyone who worked on the film found great success. “I was getting offers from all over the world,” says Sam. “It was completely unexpected. I couldn’t have been more surprised.” Gillian went on to work in Hollywood, a respected director of more than 18 films.

Miles Franklin kept writing and worked all over the world, in nursing, journalism, for the National Women’s Trade Union League in Chicago, with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals during the Serbian campaigns of 1917-18, and with the National Housing and Town Planning Council in London, concerned with women’s housing. She had the adventurous literary life she had craved. She never married.

One suspects that Miles Franklin would have been pleased that the film of her early life was made by women and that her own uncompromising leap towards independence ultimately touched so many hearts.

This article originally appeared in the August 2019 issue of The Australian Women’s Week. SUBSCRIBE so you never miss an issue